Artist's Animals. Between Abstraction, Figuration and Hybridization from the Late Twentieth Century to the Present

Abstract

‘Io son come un serpente, ogni anno cambio pelle. La mia pelle non la butto ma con essa faccio tutto.’

Pino Pascali, excerpt from the introduction to the exhibition Nuove sculture, Galleria L’Attico, Rome 1966

‘Le devenir-animal de l’homme est réel, sans que soit réel l’animal qu’il devient.’

Gilles Deleuze, Félix Guattari, Mille plateaux. Capitalisme et schizophrénie, 1980

Problematized by art (Allora & Calzadilla, 2013; Fritsch, 2013; Dion, 2011), philosophy (Despret, 2021; Nancy, 2014; Lestel, 2010) experimental poetry (Blaine, 2022) and contemporary art criticism (Ramos 2016; Teixeira Pinto, 2015; Niermann, 2013; Baker, 2000), the controversial relationship between artistic affection and animality is more than ever a rich and futurable theme of interdisciplinary perspectives and intermedial approaches. From Gerhard Richter’s photo paintings of antelopes, to Kiki Smith’s sculptures of extinct species, from Maurizio Cattelan’s installations of stuffed birds, to Berlinde De Bruyckere’s drawings of chunks of flesh, from Pierre Huyghe’s écosystèmes, to Tomás Saraceno’s spider webs, the intricate relationship between visual art and the animal imaginary continues to foster the international critical debate, establishing itself at the core of contemporary theoretical and aesthetic reflection.

The book Theater, Garden, Bestiary. A Materialist History of Exhibitions (Garcia & Normand, 2019), the exhibitions The Animal Within (Mumok, Vienna, 2022) and Animals. Respect / Harmony / Subjugation Subjugation (Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe, Hamburg, 2018), as well as the dOCUMENTA (13) in Kassel and the exhibition Zoométries. Hedendaagse Kunst in de ban van het dier (Ghent University, 2003) provide just some examples of the complex dialogue between artistic research and the animal kingdom in the twenty-first century.

The relationship between art and the concept of animality is an age-old question, whose ethical, philosophical, political, and social implications can be traced back to the avant-gardes, as shown by Hans Arp’s Cobra-Centaur (1952), Meret Oppenheim’s mug of beer with a squirrel’s tail for a handle (L’écureuil, 1960), or Unica Zürn’s phantasmagorical bestiaries (La Serpenta, 1957). The recurring image of a bird in his paintings was commented by Max Ernst in the autobiography Écritures (1970) explaining how ‘En 1930, […] j’ai eu la visite presque journalière du Supérieur des oiseaux, nommé Loplop, fantôme particulier d’une fidélité modèle, attaché à ma personne. Il me présenta un cœur en cage, la mer en cage, deux pétales, trois feuilles, une fleur et une jeune fille.’ The animal issue was examined several decades later by the neo-avant-gardes of the 1960s and 1970s, which took it as a symptom of the historical upheavals of the twentieth century, as well as of the climate crisis produced by modern technological advances.

The reflection on the natural and cultural time of the Anthropocene spurred new critical, aesthetic, and conceptual perspectives. That was the time when Joseph Beuys explained to a dead hare the meaning of some of the paintings hanging in a room (Wie man dem toten Hasen die Bilder erklärt, 1965), Nam June Paik dedicated a musical composition to plastic goldfish displayed inside a TV set-aquarium (Sonatine for Goldfish, 1975) and Jannis Kounellis exhibited a parrot on a perch fastened to a steel sheet (Pappagallo, 1967), while Valie Export was walking in the streets of Vienna with her friend Peter Weibel on a leash (From the Portfolio of Doggedness, 1968), Rebecca Horn was transforming a woman into a unicorn (Unicorn, 1970-72) and Carolee Schneemann was wrapping bodies, the remains of animals and objects in an orgiastic ritual that enacted the ancestral link between animality and eroticism (Meat Joy, 1964).

A passionate collector of cookbooks, Daniel Spoerri presented in the collection Rezept Mappen Bibliothek (1984-1990) a series of recipes classified according to the organs of the animals. This would become a recurring aspect of his artistic-literary work, from Dissertation sur le ou la Keftédès (1967), dedicated to the preparation of meatballs, to the assemblage Nature morte (1981), made with wood and fragments of pigeon eggs. The artist’s multiple, a small mobile-library consisting of a tableau-piège and ten recipe books, each dedicated to a specific ingredient, gathered texts and illustrations realized by several Neo-Avant-Garde artists, including Katharina Duwen (Lungen, Funf Szwegen Rezepte), Roland Topor (Kuttel Rezepte) and Dieter Roth (Fettflüchtigen Rezepte) i.e. the artist who, in his work, celebrated and reiterated the meeting of sculpture, chocolate and animal feed (P.O.TH.A.A.VFB, Portrait of the artist as a Vogelfutterbüste, 1968), compositions of straw and rabbit droppings (Karnickelköttelkarnickel / Bunny-dropping-bunny, 1972), installation and animal presence (Die Badewanne des Ludwig van, 1969).

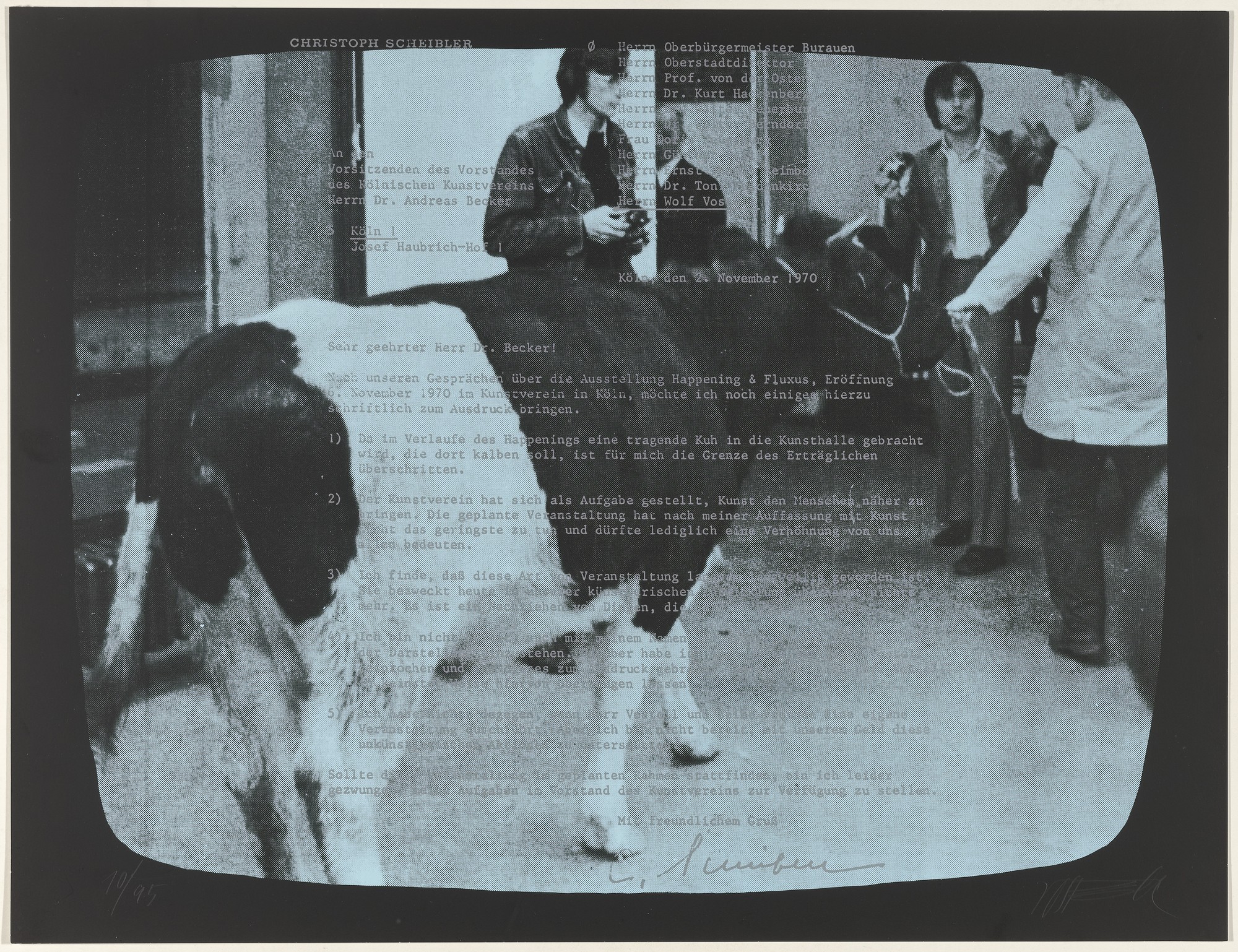

We are not so far from the turkeys of the first version of Endogene Depression (1975) that Wolf Vostell placed in a room of the Sprengel Museum in Hannover with cement and TV sets, or from the Fluxmouse no. 1 (1973) and George Maciunas’ taxonomic catalogue (Excreta Fluxorum, 1972), which contained feces collected from more than twenty insects and animals, from a beetle to a human according to their evolutionary order of development.

Once again we encounter in these works the reflection on the notion of creation and decomposition in art and in life, the fetishistic attraction for the collection and classification of organic items in their various declinations, or the neoavangardist interpretation of the animal; as Roger Caillois put it: ‘Dans tous les cas, on constate comme un génie de donner le change, de faire illusion: l’animal sait apparaître végétal ou minéral; appartenant à une espèce définie et reconnaissable, il fait croire qu’il appartient à une autre, non moins déterminée et identifiable, mais foncièrement différente’ (Le Mimétisme animal, 1963).

Viewed as mythological (Matthew Barney), totemic (Jan Fabre), autobiographical (Ana Mendieta), ludic (Jeff Koons), hybrid (Vettor Pisani), sonorous (Bruce Nauman), legendary (James Lee Byars), numerical (Mario Merz), political (Regina José Galindo), sacrificial (Hermann Nitsch) and psychoanalytical (Louise Bourgeois), animals have crossed the multiple glances of art, while being the subject of critical and philosophical speculations by writers as diverse as Donna J. Haraway (When Species Meet, 2007; The Companion Species Manifesto, 2003), Jacques Derrida (L’animal que donc je suis, 2006), and Giorgio Agamben (L’Aperto. L’uomo e l’animale, 2002).

How is the centuries-old relationship between artist and animal re-read today? How does this relationship define and continue to redefine the hybrid boundaries of art, from Rosmarie Trockel to Mircea Cantor, from Tania Bruguera to John Akomfrah? And how can we query the animal world following its shifting intentions, expressions, and figurations?

From the theories and movements of the neo-avant-garde in the 1960s and 1970s (from sculpture to performance art, from experimental poetry to photography, from installation to artists’ film), via the research of the 1980s and 1990s down to the most recent manifestations, this special issue of the journal Elephant&Castle. Laboratorio dell’immaginario gathers historical and critical contributions that take an interdisciplinary and comparative perspective on the theme of the animal in contemporary art, which we take as a sounding board for our historical actuality.

In this volume, several aspects of the debated relations between contemporary artworks, animal nature and the Anthropocene are investigated in a historical, critical, and monographic perspective. This integrated approach throws new light on some of the leading artists and poets of the 20th and 21st century, as well as on outstanding exhibitions, artists' books and critical texts devoted to the encounter between contemporary art and interspecies relationships.

The first essay focuses on Germaine Richier’s emblematic sculpture interpreted through the notion of the hybrid, i.e. the ancient idea of creatures at the intersection of the animal and human kingdom. Orane Stalpers (Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne) retraces René de Solier's interpretation of hybrid identities in art and literature through the thinking of some of the main protagonist of the avant-garde such as André Breton, Roger Caillois and Alain Jouffroy. The hybrid gathers therein references that range from magic to alchemy, myth to folklore, while presenting itself as a symbol of the tragic situation of the period.

Fascinated by elephants, in the early 1960s the visual poet Julien Blaine realized a series of performative readings of his texts that was interspersed with recordings of animal sounds expanding writing beyond the book. Julia Raymond (Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne) examines this relationship among voices, words and actions established by the artist in his experimental poetry. The author begins with a sort of transcription of the elephantine animal expression to then identify the origins and the meaning of the language - as well as its polymorphic use – in shamanic and totemic roots, providing the basis of a commonality still to be constructed outside the model of anthropologization.

In the late 1960s, Franco Vaccari produced photographs and video footage featuring animals, especially dogs. The key move was to show the world from the animals’ points of view, an identification which, while calling into question the process of human individuation, on the other hand is operated through the medium of photography. This theoretical and aesthetic path will lead the artist to his major critical work entitled Fotografia e inconscio tecnologico (1970). Valentina Rossi (Università degli Studi di Parma) reconstructs this unprecedented interpretative frame by shedding new light on the Italian artist’s research and on his refusal of the anthropocentric approach.

In the mid-1970s, it was the turn of the insects that Gianfranco Baruchello raised alive in his box constructions. As Gianlorenzo Chiaraluce (Università degli Studi ‘La Sapienza’ di Roma) points out, this was unlike the perspectives on animals that were widespread in Italy at the time, which ranged ‘from the dramaturgical and heroic dimension of Jannis Kounellis’s animals to Vettor Pisani’s mystic and alchemic dimension or Gino De Dominicis’s iconological and emblematic one.’ Baruchello instead ‘grafts with the zoological world an aesthetic procedure founded in the realm of daily experience,’ that is in a ‘real’, true cultivation, just as real as Agricola Cornelia. However, ‘real’ should not be understood in a naive sense, since this experience is turned into a work of art and into an aesthetic operation, as shown also by the paintings and collages so characteristic of Baruchello's interartistic production.

The 1970’s certainly saw an increase in the presence of the animal theme. That is in formal terms, an extension of the ready-made to the living, in opposition to the commodification of pop consumerism and in parallel to the attention to biological and linguistic corporeality. Yet also for content-related reasons, such as the attention to ecology and the abandonment of anthropomorphism. More examples arrive in that period, such as Simone Forti in the field of performance dance, analyzed by Francesca Pola (Università Vita-Salute San Raffaele, Milano) in the dimension of interspecies and ecology. At the same time Deleuze and Guattari enter the artistic and aesthetic reflection with their becoming-animal theory, articulated by Pola with Forti’s active naturality.

The 1970’s also saw Joan Fontcuberta begin his work with animals, snails in particular, even though it only really rose attention forty years later in an area he himself defined as post-photography. The process is reconstructed by Camilla Federica Ferrario (Università degli Studi ‘La Sapienza’ di Roma), following the thread of the problematization of authoriality as indicated by Fontcuberta himself. From the hybrid animal - one of the many fil rouges that characterize the texts gathered in this issue - invented by an invented naturalist, to the snails eating images, re-photographed by Fontcuberta: who is the author? A sort of interlude at this junction in the sequence of texts is the contribution by Fabriano Fabbri (Università di Bologna) who revisits the reference to animality in fashion, and elsewhere, from the early twentieth century onwards, placing it alongside that in art and framing it from the point of view of the icon/performance dichotomy. The presence of the animal in image or by mimesis is iconic, for example of cloaks and liveries or mimicking shapes and colors, whilst the means of expression is performative, at times extreme, often aggressive towards fabrics and silhouettes that emerge ill-treated with rips and torn edges. Fabbri’s understanding of both art and fashion ensures that he gives the right emphasis to the dialectic bidirectionality of the influence between the two. Certainly, the reference to the animal in fashion goes, as Fabbri shows, not so much in the direction of the extravagance of the garment but in that of the liberation of the body.

With Chris Marker we move on to the cinema: his Petit Bestiaire (1990) compares the gaze of the animal with that of the camera, in a kind of oscillation between the famous observations of Jacques Derrida on one hand and John Berger on the other. Rosemary O’Neill (Parsons School of Design – The New School) describes it as an oscillation between ‘the limits of human knowledge of animal alterities and an evocation of the possibility of awareness of shared interrelations,’ on which plays a possible égalité du regard.

The title of the text by Caterina Iaquinta (Nuova Accademia di Belle Arti di Milano, NABA) says it all: Appunti per un bestiario femminista. Clemen Parrocchetti artista oltre il divenire-animale. And what is beyond the becoming-animal from the feminist point of view? Naturally, the becoming-woman. From the start the stakes are high: ‘together with many artists of her generation [1923] Italian and international, she pursues an irregular direction for her time.’ In that irregularity there is a feminine and feminist character. For Parrocchetti it takes form in her relation with the animal in the 1990’s, when at the center of her work, beginning with the autobiographical theme, she explores those of the ‘problematicity linked to the construction of the image of the animal in relation to oneself; the possible inscription of the animal as a social and ecological subject, and the processes of transformativity, metamorphosis (we would say today interspeciesism) that regard the world of arthropods and micro-organisms.’ Feminism and in particular eco-feminism become the keys to rereading the becoming-woman in a close comparison with the body and the animal.

Several artists have explored the delicate theme of hunting, in many regards opposed to but in others in dialectic with that of animality, and Luca Bochicchio (Università degli Studi di Verona) for his part confronts it head on. Some very interesting questions emerge from an analysis of Hanging Carousel (George Skins a Fox) by Bruce Nauman (1988) alongside Redoubt by Matthew Barney (2018). It is interesting to note that one of them was produced in the late 1980’s, just around the time of the posthuman wave, and the other, made indeed by of one of the champions of posthumanism, was produced at a time when it was evolving further. The fact is that hunting is linked to ancestral themes on one hand and identity on the other; it is anthropological on one side and historic-social on the other, especially in the North American context.

Bochicchio summarizes: ‘hunting, treated as a symbolic ritual (with its various objectual, processual, technical, and technological appurtenances), enters the works of Bruce Nauman (Fort Wayne, Indiana, 1941) and Matthew Barney (San Francisco, California, 1967) as the derivation of a discourse on culture and identity that is typically North American, and is re-elaborated and mediated through ancient myth. The breadth of this discourse occupies current debate, going back to the same existential arguments of the American nation.’

The special issue concludes with a piece by Marie-Laure Delaporte (Université Paris Nanterre) who revisits and links various themes from the other texts. It is curious to note the interest that the different artists have had for the elephant. This is surely because it has maintained characteristics that seem prehistoric, in the fullest sense of the word, which encompasses pre and post. In fact, Delaporte remarks that the artist Marguerite Humeau inserts it in the dialectic not only between science and myth, but also between extinction and resurrection in the perspective of a post-animal world. Indeed, the most recent issue at stake goes under the notion of the anthropocene and everything is to be reconsidered in a flip of perspective where before and after can no longer be thought of in a linear way.

This perhaps is what the animal debate definitively teaches us, while what recent artists put to us is that the question cannot be examined without a complex range of technical and cultural working tools, which to define as interdisciplinary would not nearly be enough. Let us end with the closing words of Delaporte’s text: ‘The material artwork has been replaced by a performance that tells the tale of the absent animal, at a time of disappearing in which art attempts to avoid the end of time.’

ELIO GRAZIOLI (Università degli Studi di Bergamo)

MARIA ELENA MINUTO (Université de Liège; KU Leuven)

BIBLIOGRAPHY

AGAMBEN G. (2002). L’Aperto. L’uomo e l’animale. Turin: Bollati Boringhieri.

BAKER S. (2000). Postmodern Animal. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

BLAINE J. (2022). Julien Blaine présente quelques-uns de ses amis Animaux-&-artistes. Paris: Les presses du réel.

CHELBI S. (1999). Figures de l’animalité dans l’œuvre de Michel Foucault. Paris: L’Harmattan.

CAILLOIS R. (1963). Le Mimétisme animal. Paris: Hachette.

DELEUZE G., GUATTARI F. (1980). Mille plateaux. Capitalisme et schizophrénie. Paris: Éditions de Minuit.

DERRIDA J. (2006). L’animal que donc je suis. Paris: Éditions Galilée.

DESPRET V. (2021). Autobiographie d'un poulpe et autres récits d'anticipation. Arles: Actes Sud.

DESPRET V., PORCHER J. (2007). Être bête. Arles: Actes Sud.

FONFROIDE R. (2009). ‘Gloria Friedmann et Alain Rivière-Lecoeur. Hommes et animaux dans l’art contemporain: la question de la métaphore trouble.’ In Sociétés et representations, n. 27. Paris: Nouveau monde.

FORBES D., JANSEN D. (2015). Beastly / Tierisch. Exhibition Catalogue. Fotomuseum Winterthur, 30.05 – 11.10.2015. Leipzig: Spector Books.

GARCIA T., NORMAND V. (2019). Theater, Garden, Bestiary. A Materialist History of Exhibitions. Berlin: Sternberg Press.

HARAWAY D. J. (2007). When Species Meet. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

HARAWAY D. J. (2003). The Companion Species Manifesto. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

JEANGÈNE VILMER J. B. (2009). ‘Animaux dans l’art contemporain, la question éthique.’ In Jeu. Revue de théâtre, n. 130, pp. 40-47.

LESTEL D. (2010). L’animal est l’avenir de l’homme. Paris: Éditions Fayard.

MAILLET M. L. (1999). L’Animal autobiographique. Autour de Jacques Derrida. Paris: Éditions Galilée.

NANCY J. L. (2014). ‘Oh the Animals of Language.’ In e-flux Journal, Issue #65, May 2015.

RAMOS F. (2016). Animals. Cambridge: MIT Press.

SUBRIZI C. (2019). ‘Carol Rama e l’animale: divenire donna e femminismo negli anni novanta.’ In Boletín de Arte, n. 40, Departamento de Historia del Arte, Universidad de Malaga, pp. 61-67.

TEXTEIRA PINTO A. (2015). ‘The Post-Human Animal.’ In RAMOS F. (ed.) (2016). Animals. Cambridge: MIT Press, pp. 106-109.

VAN DAMME C., VAN ROSSEM P., MARCHAND C. (2005). Zoométries: Hedendaagse Kunst in De Ban Van Het Dier. Gent: LKG Publication (UGent Leerstoel Karel Geirlandt) and Gent Academia Press.

VIRILIO P. (1977). ‘Métempsycose du passager.’ In Les Bêtes. Traverses, n° 8, 2e trimestre, p .16.

Downloads

Published

How to Cite

Issue

Section

License

Copyright (c) 2023 Elephant & Castle

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.